Courage Under Fire

| Courage Under Fire | |

|---|---|

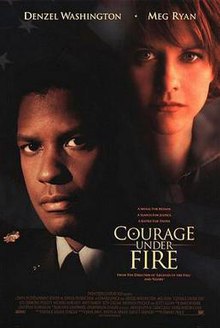

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Edward Zwick |

| Written by | Patrick Sheane Duncan |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Roger Deakins |

| Edited by | Steven Rosenblum |

| Music by | James Horner |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release date |

|

Running time | 116 minutes |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $46 million[1] |

| Box office | $100.9 million |

Courage Under Fire is a 1996 American war drama film directed by Edward Zwick, and starring Denzel Washington and Meg Ryan. It is the second collaboration between Washington and director Zwick. The film was released in the United States on July 12, 1996, to positive reviews and grossed $100 million worldwide.

Plot

[edit]While serving in the Persian Gulf War, Lieutenant Colonel Nathaniel Serling fires on and destroys one of his own tanks during a confusing nighttime battle, killing his friend, Lieutenant Tom Boylar. The United States Army covers up the friendly fire incident, awards Serling a medal for bravery, and transfers him to a desk job.

Later, Serling is assigned to determine if, posthumously, Captain Karen Walden should be the first woman to receive the Medal of Honor. She was the commander of a Medevac Huey helicopter sent to rescue the crew of a shot-down Black Hawk helicopter. When Walden encountered an enemy T-54 tank, her crew destroyed it by dropping a fuel bladder onto the tank and igniting it with a flare gun. Her own helicopter was shot down soon after. The two crews were unable to join forces, and when the survivors were rescued the next day, Walden was reported dead.

Serling notices inconsistencies among the testimonies of Walden's crew. Specialist Andrew Ilario, the medic, praises Walden strongly. Staff Sergeant John Monfriez claims that Walden was a coward and that he led the crew in combat and improvised the fuel bladder weapon. Sergeant Steven Altameyer, who is dying of cancer in a hospital and was initially hard for Serling to find, complains about a fire in one of his few coherent comments. Warrant Officer Rady, the co-pilot, was injured early on and was unconscious throughout the ordeal. The crew of the Black Hawk claim that they heard firing from an M16 rifle, but Ilario and Monfriez claim it was out of ammo.

Serling is under pressure from the White House and his commander, Brigadier General Hershberg, to wrap things up quickly. Feeling guilty about the cover up in the friendly fire incident, Serling leaks the existence of a tape of the attack to newspaper reporter Tony Gartner. When Serling grills Monfriez during a car ride, Monfriez forces him to get out of the vehicle at gunpoint, then commits suicide by driving into an oncoming train.

Serling tracks Ilario down, and Ilario finally tells him the truth. Monfriez wanted to flee, which would mean abandoning Rady. When Walden refused, he pulled a gun on her and Walden threatened him with a court-martial for mutiny and ordered that he surrender his gun. During the stand-off over Monfriez's gun Walden shot an enemy who suddenly appeared behind Monfriez; Monfriez thinking it was Walden firing at him shot her in the stomach, before backing off. The next morning, the enemy attacked again as a rescue party approached. Walden covered her men's retreat, firing an M16. Monfriez told the rescuers that Walden was dead, so they left without her. Napalm was then dropped on the entire area. Altameyer tried to expose Monfriez's lie at the time, but was too injured to speak, and Ilario remained silent, scared of the court-martial Walden had threatened them with.

Serling presents his final report to Hershberg. Walden's young daughter receives the Medal of Honor at a White House ceremony. Later, Serling tells the truth to the Boylars about the manner of their son's death and says he cannot ask for forgiveness. The Boylars forgive him.

In the last moments, Serling has a flashback of when he was standing by Boylar's destroyed tank and a medevac Huey was lifting off with his friend's body. Serling suddenly realizes Walden was the pilot. At that moment he is able to let go of the feelings that he has developed for her, and returns to his family.

Cast

[edit]- Denzel Washington as Lieutenant Colonel Nathaniel Serling

- Meg Ryan as Captain Karen Emma Walden

- Lou Diamond Phillips as Staff Sergeant John Monfriez

- Matt Damon as Specialist Andrew Ilario

- Bronson Pinchot as Bruno, a White House aide

- Seth Gilliam as Sergeant Steven Altameyer

- Regina Taylor as Meredith Serling

- Michael Moriarty as Brigadier General Hershberg

- Željko Ivanek as Captain Ben Banacek

- Scott Glenn as Tony Gartner, a Washington Post reporter and Vietnam veteran

- Tim Guinee as Warrant Officer One A. Rady

- Tim Ransom as Captain Boylar

- Sean Astin as Private Patella

- Ned Vaughn as First Lieutenant Chelli

- Sean Patrick Thomas as Sergeant Thompson

- Manny Pérez as Jenkins

- Ken Jenkins as Joel Walden

- Kathleen Widdoes as Geraldine Walden

- Christina Stojanovich as Anne Marie Walden

- Diane Baker as Louise Boylar

- Richard Venture as Don Boylar

- Tom Schanley as Questioner

- Korey Coleman as Radio operator

- David McSwain as Sergeant Egan

Members of the Corps of Cadets of Texas A&M University were cast as soldiers in the basic training scenes.

Production

[edit]The Pentagon denied a request for access to military equipment for filming. Philip M. Strub, for the Pentagon, said of the film characters that "there wasn't a good soldier among them".[2] Lacking such access, the film-makers had to source equipment elsewhere, including having former Australian Army Centurian tanks modified to resemble the M1 Abrams depicted in the production.[3]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]- U.S. domestic gross: US$ 59,031,057 [4]

- International: $41,829,761[4]

- Worldwide gross: $100,860,818[4]

The film opened #3 at the box office behind Independence Day and Phenomenon.[5]

Critical response

[edit]The film received mostly positive reviews. As of June 15, 2022, the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reported that 86% of critics gave the film a positive review based upon a sample of 56 reviews with an average rating of 7.3/10. The critical consensus states that the film is "an emotional and intriguing tale of a military officer who must review the merits of a fallen officer while confronting his own war demons. Effectively depicts the terrors of war as well as its heartbreaking aftermath."[6] At the website Metacritic, which uses a weighted average rating system, the film earned a generally favorable rating of 77/100 based on 19 mainstream critic reviews.[7] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A" on an A+ to F scale.[8]

The movie was commended by several critics. James Berardinelli of the website ReelViews wrote that the film was, "As profound and intelligent as it is moving, and that makes this memorable motion picture one of 1996's best."[9] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times spoke positively of the film saying that while the ending "lays on the emotion a little heavily" the movie had been up until that point "a fascinating emotional and logistical puzzle—almost a courtroom movie, with the desert as the courtroom."[10]

Denzel Washington's acting was specifically lauded, as Peter Travers of Rolling Stone wrote, "In Washington's haunted eyes, in the stunning cinematography of Roger Deakins (Fargo) that plunges into the mad flare of combat, in the plot that deftly turns a whodunit into a meditation on character and in Zwick's persistent questioning of authority, Courage Under Fire honors its subject and its audience."[11] Additionally Peter Stack of the San Francisco Chronicle wrote that "Denzel Washington is riveting."[12]

Matt Damon, on his way to stardom but not there yet, said he lost 40 pounds for his role despite only being scheduled for two days of shooting opposite Washington. When critics and reporters rarely mentioned his appearance in the film, Damon said he contemplated suicide for feeling so overlooked, even though A-List Steven Spielberg would later compliment Damon for his performance and cast him as the titular character in the war epic Saving Private Ryan. After getting medicated, his mental health improved, along with his career recognition and prospects.[13]

Accolades

[edit]Denzel Washington was nominated for Best Actor at the 1996 Chicago Film Critics Association Awards, but lost to Billy Bob Thornton in Sling Blade.

Historical context

[edit]The Medal of Honor was awarded to Mary Edwards Walker, an American Civil War physician, but not for valor in combat.[14] Her name was deleted from the Army Medal of Honor Roll in 1917 (along with over 900 other recipients); however, it was restored in 1977.[15]

References

[edit]- ^ "Courage Under Fire (1996) - Financial Information". the-numbers.com.

- ^ Seeyle, Katharine Q. (June 10, 2002). "When Hollywood's Big Guns Come Right From the Source". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 30, 2018.

- ^ [1]

- ^ a b c Courage Under Fire – Box Office Data, DVD Sales, Movie News, Cast Information. The Numbers. Retrieved on May 11, 2013.

- ^ "July 12–14, 1996". boxofficemojo.com. Retrieved October 31, 2011.

- ^ "Courage Under Fire Movie Reviews". Rotten Tomatoes. IGN Entertainment. Archived from the original on March 27, 2009. Retrieved August 13, 2009.

- ^ "Courage Under Fire Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved August 13, 2009.

- ^ "Home". CinemaScore. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ^ Berardinelli, James (July 1996). "Courage under Fire". ReelViews. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (July 12, 1996). "Courage Under Fire". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved August 13, 2009.

- ^ Travers, Peter (July 12, 1996). "Courage under Fire". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on December 28, 2009. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- ^ Stack, Peter (July 12, 1996). "Fired-Up Over 'Courage'". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved August 13, 2009.

- ^ "Robin Williams and Matt Damon Interview for Good Will Hunting (1998)". The Charlie Rose Show. PBS. Retrieved October 28, 2024.

- ^ "Highest Medal Restored to War Heroine". The New York Times. June 11, 1977. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 3, 2018.

- ^ Pennington, Reina (2003). Amazons to Fighter Pilots - A Biographical Dictionary of Military Women (Volume Two). Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 474–475. ISBN 0-313-32708-4.

External links

[edit]- 1996 films

- 1996 action films

- 1990s war films

- 1990s action drama films

- American political drama films

- American war films

- 1990s English-language films

- Films about armoured warfare

- Films directed by Edward Zwick

- Films produced by John Davis

- Films scored by James Horner

- Films set in Iraq

- Films set in the United States

- Films shot in Connecticut

- Films shot in El Paso, Texas

- Gulf War films

- 20th Century Fox films

- Davis Entertainment films

- Films about the United States Army

- 1990s political drama films

- 1996 drama films

- 1990s American films

- English-language action drama films

- English-language war films