Economy of Russia

| |

| Currency | Russian ruble (RUB or руб or ₽) |

|---|---|

| Calendar year[1] | |

Trade organizations | WTO, BRICS, EAEU, CIS, GECF, APEC, G20 and others |

Country group |

|

| Statistics | |

| Population | |

| GDP | |

| GDP rank | |

GDP growth |

|

GDP per capita | |

GDP per capita rank | |

GDP by sector |

|

| |

Population below poverty line | |

Labor force | |

Labor force by occupation |

|

| Unemployment |

|

Average gross salary | RUB 85,017 / €802 per month |

| RUB 73,965 / €698 per month | |

Main industries | Complete range of mining and extractive industries producing coal, oil, gas, chemicals, and metals; all forms of machine building from rolling mills to high-performance aircraft and space vehicles; defence industries (including radar, missile production, advanced electronic components), shipbuilding; road and rail transportation equipment; communications equipment; agricultural machinery, tractors, and construction equipment; electric power generating and transmitting equipment; medical and scientific instruments; consumer durables, textiles, foodstuffs, handicrafts |

| External | |

| Exports | |

Export goods | Crude petroleum, refined petroleum, natural gas, coal, wheat, iron (2019) |

Main export partners |

|

| Imports | |

Import goods | Cars and vehicle parts, packaged medicines, broadcasting equipment, aircraft, computers (2019) |

Main import partners |

|

FDI stock | |

Gross external debt | |

| Public finances | |

| 3.8% of GDP (2022)[21] | |

| Revenues | |

| Expenses | |

All values, unless otherwise stated, are in US dollars. | |

The economy of Russia is an emerging and developing,[2] high-income,[27] industrialized,[28] mixed market-oriented economy.[29] It has the eleventh-largest economy in the world by nominal GDP and the fourth-largest economy by GDP (PPP).[5] Due to a volatile currency exchange rate, its GDP measured in nominal terms fluctuates sharply.[30] Russia was the last major economy to join the World Trade Organization (WTO), becoming a member in 2012.[31]

Russia has large amounts of energy resources throughout its vast landmass, particularly natural gas and petroleum, which play a crucial role in its energy self-sufficiency and exports.[32] The country has been widely described as an energy superpower;[33] with it having the largest natural gas reserves in the world,[34] the second-largest coal reserves,[35] the eighth-largest oil reserves,[36] and the largest oil shale reserves in Europe.[37] Russia is the world's leading natural gas exporter,[38] the second-largest natural gas producer,[39] the second-largest oil exporter[40] and producer,[41] and the third-largest coal exporter.[42] Its foreign exchange reserves are the fourth-largest in the world.[43] Russia has a labour force of about 72 million people, which is the eighth-largest in the world.[11] It is the third-largest exporter of arms in the world.[44] The oil and gas industry accounted up to 41% of Russia's federal budget revenues by mid-2024,[45] while fossil fuels accounted up to 43% of its merchandise exports in 2021.[46]

Russia's human development is ranked as "very high" in the annual Human Development Index.[47] Roughly 70% of Russia's total GDP is driven by domestic consumption,[48] and the country has the world's twelfth-largest consumer market.[49] Its social security system comprised roughly 16% of the total GDP in 2015.[50] Russia has the fifth-highest number of billionaires in the world.[51] However, its income inequality remains comparatively high,[52] caused by the variance of natural resources among its federal subjects, leading to regional economic disparities.[53][54] High levels of corruption,[55] a shrinking labor force,[56] and an aging and declining population also remain major barriers to future economic growth.[57][58]

Following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the country has faced extensive sanctions and other negative financial actions from the Western world and its allies which have the aim of isolating the Russian economy from the Western financial system.[59] However, Russia's economy has shown resilience to such measures broadly, and has maintained economic stability and growth—driven primarily by high military expenditure,[60] rising household consumption and wages,[61] low unemployment,[13] and increased government spending.[62] Yet, experts predict the sanctions will have a long-term negative effect on the Russian economy.[63]

History

The Russian economy has been volatile over the past multiple decades. After 1989, its institutional environment was transformed from a command economy based upon socialist organizations to a capitalistic system. Its industrial structure dramatically shifted away over the course of several years from heavy investment in manufacturing as well as in traditional Soviet agriculture towards free market related developments in natural gas and oil extraction in additional to businesses engaged in mining. A service economy also expanded during this time. The academic analyst Richard Connolly has argued that, over the last four centuries in a broad sense, there were four main characteristics of the Russian economy that have shaped the system and persisted despite the political upheavals. First of all the weakness of the legal system means that impartial courts do not rule and contracts are problematic. Second is the underdevelopment of modern economic activities, with very basic peasant agriculture dominant into the 1930s. Third is technological underdevelopment, eased somewhat by borrowing from the West in the 1920s. And fourth lower living standards compared to Western Europe and North America.[64]

Russian Empire

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The economy of the Russian Empire covers the economic history of Russia from 1721 to the October Revolution of 1917 (which ushered in a period of civil war, culminating in the creation of the Soviet Union).

Russian national income per capita increased and moved to closer to the most developed economies of Northern and Western Europe from the late 17th century to the mid 18th century.[65][66] After the mid 18th century, the Russian economy stagnated and declined.[65][66] In the 18th century, Russian national income per capita was about 40–70% of British per capita income but higher than Poland's.[65] By 1860, Russian GDP per capita was similar to that of Japan; one-third of GDP per capita in the United States or the United Kingdom; and twice that of China or India.[65] Russia was a late industrializer.[65] Over the course of the late 19th century and early 20th century, Russia's railroad system expanded considerably, enabling greater industrialization.[67]

Serfdom, which held back development of the wage labor market and created a shortage of labor for industry, was abolished in 1861.[65][66] In the aftermath, GDP per capita was volatile and did not substantially increase.[65][66] Steady economic growth began in the 1890s, alongside a structural transformation of the Russian economy.[65] By the time World War I started, more than half the Russian economy was still devoted to agriculture.[65][68] By the early 20th century, the Russian economy had fallen further behind the American and British economies.[65] From the late 19th century to the early 20th century, the economy grew at a similar pace as the Japanese economy and faster than the Brazilian, Indian and Chinese economies.[65]Soviet Union

Beginning in 1928, the course of the Soviet Union's economy was guided by a series of five-year plans. By the 1950s, the Soviet Union had rapidly evolved from a mainly agrarian society into a major industrial power.[69] By the 1970s the Soviet Union was in an Era of Stagnation. The complex demands of the modern economy and inflexible administration overwhelmed and constrained the central planners. The volume of decisions facing planners in Moscow became overwhelming. The cumbersome procedures for bureaucratic administration foreclosed the free communication and flexible response required at the enterprise level for dealing with worker alienation, innovation, customers, and suppliers.

From 1975 to 1985, corruption and data manipulation became common practice within the bureaucracy to report satisfied targets and quotas, thus entrenching the crisis. Starting in 1986, Mikhail Gorbachev attempted to address economic problems by moving towards a market-oriented socialist economy. Gorbachev's policies of Perestroika failed to rejuvenate the Soviet economy; instead, a process of political and economic disintegration culminated in the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Transition to market economy (1991–1998)

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia underwent a radical transformation, moving from a centrally planned economy to a globally integrated market economy. Corrupt and haphazard privatization processes turned over major state-owned firms to politically connected "oligarchs", which has left equity ownership highly concentrated.

Yeltsin's program of radical, market-oriented reform came to be known as a "shock therapy". It was based on the policies associated with the Washington Consensus, recommendations of the IMF and a group of top American economists, including Larry Summers[70][71][72] who in 1994 urged for "the three '-ations'—privatization, stabilization, and liberalization" to be "completed as soon as possible."[73] With deep corruption afflicting the process, the result was disastrous, with real GDP falling by more than 40% by 1999, hyperinflation which wiped out personal savings, crime and destitution spreading rapidly.[74][75] The jump in prices from shock therapy wiped out the modest savings accumulated by Russians under socialism and resulted in a regressive redistribution of wealth in favour of elites who owned non-monetary assets.[76]

Shock therapy was accompanied by a drop in the standard of living, including surging economic inequality and poverty,[77] along with increased excess mortality[78][79][80] and a decline in life expectancy.[81] Russia suffered the largest peacetime rise in mortality ever experienced by an industrialized country.[82] Likewise, the consumption of meat decreased: in 1990, an average citizen of the RSFSR consumed 63 kg of meat a year; by 1999, it had decreased to 45 kg.[83]

The majority of state enterprises were privatized amid great controversy and subsequently came to be owned by insiders[84] for far less than they were worth.[71] For example, the director of a factory during the Soviet regime would often become the owner of the same enterprise. Under the government's cover, outrageous financial manipulations were performed that enriched a narrow group of individuals at key positions of business and government.[85] Many of them promptly invested their newfound wealth abroad, producing an enormous capital flight.[86] This rapid privatization of public assets, and the widespread corruption associated with it, became widely known throughout Russia as "prikhvatizatisiya," or "grab-itization."[87]

Difficulties in collecting government revenues amid the collapsing economy and dependence on short-term borrowing to finance budget deficits led to the 1998 Russian financial crisis.

In the 1990s, Russia was a major borrower from the International Monetary Fund, with loan facilities totalling $20 billion. The IMF was criticised for lending so much, as Russia introduced little of the reforms promised for the money and a large part of these funds could have been "diverted from their intended purpose and included in the flows of capital that left the country illegally".[88][89]

On 24 September 1993, at a meeting of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) Council of Heads of State in Moscow, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan signed the Treaty on the creation of an Economic Union which reinforces by an international agreement the intention to create an economic union through the step-by-step creation of a free trade area, a customs union and conditions for the free movement of goods, services, capital and labor. All these countries have ratified the Treaty and it entered into force on 14 January 1994. Turkmenistan[90] and Georgia joined in 1994 and ratified the Treaty, but Georgia withdrew in 2009.[91]

On 15 April 1994, at a meeting of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) Council of Heads of State in Moscow, all 12 post-Soviet states signed the international Agreement on the Establishment of a Free Trade Area in order to move towards the creation of an economic union. Article 17 also confirmed the intention to conclude a free trade agreement in services.[92] Article 1 indicated that this was "the first stage of the creation of the Economic Union", but in 1999 the countries agreed to remove this phrase from the agreement. [93] Russia concluded bilateral free trade agreements with all CIS countries and did not switch to a multilateral free trade regime in 1999. Bilateral free trade agreements, except for Georgia, Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan[94][95] (all of these are in force as of 2024), ceased to apply only after 2012 with Russia's accession to the new multilateral CIS free trade area.

Further integration took place outside the legal framework of the CIS. Pursuant to the Treaty on the creation of an Economic Union, the Agreement on the Customs Union between the Russian Federation and the Republic of Belarus was signed on 6 January 1995 in Minsk.[96] The Government of the Republic of Belarus and the Government of the Russian Federation, on the one side, and the Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan, on the other side, signed an Agreement on the Customs Union in Moscow on 20 January 1995 in order to move towards the creation of an economic union as envisaged by the treaty.[97] The implementation of these agreements made it possible to launch the Customs Union of the Eurasian Economic Community in 2010. According to the database of international treaties of the Eurasian Economic Union, these agreements are still in force as of 2024 and apply in part not contrary to the Treaty on the Eurasian Economic Union. [98][99][100]

International agreements such as the following have further deepened trade and economic relations and integration with Belarus. The Community of Belarus and Russia was founded on 2 April 1996. The "Treaty on the Union between Belarus and Russia" was signed on 2 April 1997. And finally the Treaty on the Creation of a Union State of Russia and Belarus was signed on 8 December 1999.

Recovery and growth (1999–2008)

Russia recovered quickly from the August 1998 financial crash, partly because of a devaluation of the ruble, which made domestic producers more competitive nationally and internationally.

Between 2000 and 2002, significant pro-growth economic reforms included a comprehensive tax reform, which introduced a flat income tax of 13%; and a broad effort at deregulation which benefited small and medium-sized enterprises.[101]

Between 2000 and 2008, Russian economy got a major boost from rising commodity prices. GDP grew on average 7% per year.[74] Disposable incomes more than doubled and in dollar-denominated terms increased eightfold.[102] The volume of consumer credit between 2000 and 2006 increased 45 times, fuelling a boom in private consumption.[103][104] The number of people living below poverty line declined from 30% in 2000 to 14% in 2008.[105][106]

Russia repaid its borrowing of $3.3 billion from the IMF three years early in 2005.[107]

Inflation remained a problem however, as the central bank aggressively expanded money supply to combat appreciation of the ruble.[108] Nevertheless, in 2007 the World Bank declared that the Russian economy achieved "unprecedented macroeconomic stability".[109] Until October 2007, Russia maintained impressive fiscal discipline with budget surpluses every year from 2000.[101]

2009–2014

Russian banks were affected by the 2007–2008 financial crisis, though no long term damage was done due to a proactive and timely response by the government and central bank.[110][111][112] A sharp, but brief recession in Russia was followed by a strong recovery beginning in late 2009.[74]

Between 2000 and 2012, Russia's energy exports fuelled a rapid growth in living standards, with real disposable income rising by 160%.[113] In dollar-denominated terms this amounted to a more than sevenfold increase in disposable incomes since 2000.[102] In the same period, unemployment and poverty more than halved and Russians' self-assessed life satisfaction also rose significantly.[114] This growth was a combined result of the 2000s commodities boom, high oil prices, as well as prudent economic and fiscal policies.[115] However, these gains have been distributed unevenly, as the 110 wealthiest individuals were found in a report by Credit Suisse to own 35% of all financial assets held by Russian households.[116][117] Russia also has the second-largest volume of illicit money outflows, having lost over $880 billion between 2002 and 2011 in this way.[118] Since 2008 Forbes has repeatedly named Moscow the "billionaire capital of the world".[119]

In July 2010, Russia, together with Belarus and Kazakhstan, became a founding member of the Customs Union of the Eurasian Economic Community (EurAsEC), and the EurAsEC Single Economic Space, a common market of the same countries, came into force on 1 January 2012, superseding the bilateral agreements on free trade. At the same time Russia's membership to the WTO was accepted in 2011.[120] Russia joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) on 22 August 2012 after 19 years of negotiations.[121][122][123] On 20 September 2012, the multi-lateral Free Trade Area of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS FTA) came into force for Russia and subsequently superseded previous bilateral agreements among 9 participating post-Soviet states.[124] In 2015, Russia became a founding member of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), which replaced EurAsEC and envisaged a supranational economic union (the deepest stage of economic integration[125]).[126]

Rapid GDP and income growth continued until 2013. The most important topic of discussion in the economy for a decade was the middle-income trap. In 2013, the World Bank announced that Russia had graduated to a high-income economy based on the results of 2012[127][128][129] but in 2016 it was reclassified as an upper-middle income economy[130][131] due to changes in the exchange rate of the Russian ruble, which is a floating currency. While the UN Human Development Index, which assesses progress in the standard of living, health and education, ranks Russia among the 'very high human development' countries.[132][133]

Russian leaders repeatedly spoke of the need to diversify the economy away from its dependence on oil and gas and foster a high-technology sector.[134] In 2012 oil, gas and petroleum products accounted for over 70% of total exports.[135] This economic model appeared to show its limits, when after years of strong performance, the Russian economy expanded by a mere 1.3% in 2013.[74] Several reasons were proposed to explain the slowdown, including a prolonged recession in the EU, which is Russia's largest trading partner, stagnant oil prices, lack of spare industrial capacity and demographic problems.[136] Political turmoil in neighbouring Ukraine added to the uncertainty and suppressed investment.

2014–2021

Following the annexation of Crimea in March 2014 and Russia's involvement in the ongoing War in Donbas, the United States, the European Union, Canada, and Japan imposed sanctions on Russia.[137] This led to the decline of the Russian ruble and sparked fears of a Russian financial crisis. Russia responded with sanctions against a number of countries, including a one-year period of total ban on food imports from the European Union and the United States.

According to the Russian economic ministry in July 2014, GDP growth in the first half of 2014 was 1%. The ministry projected growth of 0.5% for 2014.[138] The Russian economy grew by a better than expected 0.6% in 2014.[139] Russia is rated one of the most unequal of the world's major economies.[140]

As a result of the World Bank's designation of a high-income economy, Barack Obama issued a proclamation 9188: "I have determined that Russia is sufficiently advanced in economic development and improved in trade competitiveness that it is appropriate to terminate the designation of Russia as a beneficiary developing country effective October 3, 2014."[141] U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) indicated that Russia formally graduated from the GSP program on 4 October 2014.[142]

As of 2015, real income was still lower for 99% of Russians than it was in 1991.[82]

The Russian economy risked going into recession from early 2014, mainly due to falling oil prices, sanctions, and the subsequent capital flight.[143] While in 2014 GDP growth remained positive at 0.6%,[144] in 2015 the Russian economy shrunk by 3.7% and was expected to shrink further in 2016.[145] By 2016, the Russian economy rebounded with 0.3% GDP growth and officially exited recession. The growth continued in 2017, with an increase of 1.5%.[146][147]

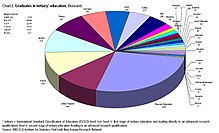

In January 2016, Bloomberg rated Russia's economy as the 12th most innovative in the world,[148] up from 14th in January 2015[149] and 18th in January 2014.[150] Russia has the world's 15th highest patent application rate, the 8th highest concentration of high-tech public companies, such as internet and aerospace and the third highest graduation rate of scientists and engineers.[148]

According to the British company BP (Statistical Yearbook 2018), proven oil reserves in Russia at the end of 2017 were 14.5 billion tonnes (14.3 billion long tons; 16.0 billion short tons), natural gas was 35 trillion cubic metres (1.2 quadrillion cubic feet).[151] Gold reserves in Russia's subsoil, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, were 5,500 tonnes (5,400 long tons; 6,100 short tons) at the end of 2017.[152]

In 2019, the Ministry of Natural Resources estimated the country's mineral reserves in physical terms. At the end of 2017, oil reserves were 9.04 billion tonnes (8.90 billion long tons; 9.96 billion short tons), gas reserves were 14.47 trillion cubic metres (511 trillion cubic feet), gold reserves were 1,407 tonnes (1,385 long tons; 1,551 short tons), and diamonds reserves were 375 million carats (75 tonnes). Then for the first time the Ministry evaluated the mineral reserves of Russia in terms of value. The value of oil reserves amounted to 39.6 trillion rubles, the value of gas amounted to 11.3 trillion rubles, coking coal amounted to almost 2 trillion rubles, iron ore amounted to 808 billion rubles, diamonds amounted to 505 billion rubles, gold amounted to 480 billion rubles. The combined value of all mineral and energy resources (oil, gas, gold, copper, iron ore, thermal and lignite coal, and diamonds) amounted to 55.24 trillion rubles (US$844 billion), or 60% of GDP for 2017. The assessment occurred after the adoption of a new classification of reserves in Russia and the object of the methodology was only those fields for which a license was issued, so the assessment of the Ministry of Natural Resources is less than the total volume of explored reserves. Experts criticized such "an unsuccessful attempt to estimate reserves," pointing out that "one should not take such an estimate seriously" and "the form contains an incorrect formula for calculating the value".[153][154]

In the International Comparison Program 2021, the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) region was linked through the standard global core list approach, unlike in ICP 2017. Based on the results, the World Bank announced that in 2021 Russia was the 4th largest economy in the world ($5.7 trillion and 3.8 percent of the world) and the largest economy in Europe and Central Asia when measured in PPP terms.[155]

2022–present

In 2022, heavy sanctions were enacted due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine which will likely result in a steep recession.[157] Since early 2022, many official economic statistics have not been published.[158] Sanctions also included asset freezes on the Russian Central Bank,[159] which holds $630 billion in foreign-exchange reserves,[160] to prevent it from offsetting the effects of sanctions.[161]

According to most estimates, every day of the war in Ukraine costs Russia $500 million to $1 billion.[162][163][164]

On 27 June 2022, Russia defaulted on part of its foreign currency, its first such default since 1918.[165]

In November 2022, it was reported that Russia had officially entered a recession as the Federal State Statistics Service had reported a national GDP loss for the second consecutive quarter.[166]

As part of the sanctions imposed on Russia, on 2 September 2022, the finance ministers of the G7 group agreed to cap the price of Russian oil and petroleum products, designed to allow Russia to maintain production, but limiting revenue from oil sales.[167][168]

In 2022, The Economist calculated that Russia did graduate into the category of high-income economies by 2022, if counted at purchasing power parity rather than the exchange rate but could fall below the threshold due to the invasion of Ukraine.[169] In December 2022, a study at Bank of Russia's Research and Forecasting Department, found that the import dependence of the Russian economy is relatively low, does not exceed the median for other countries, and the share of imports in most industries is lower than in other countries. The key explanation for this could be the low involvement of the Russian economy in global value supply chains and its focus on production of raw materials. However, 60% of Russia's imports come from the countries that have announced sanctions against Russia.[170]

TASS reported poor results for the Russian economy the first quarter of 2023 with revenue of 5.7 trillion roubles – down 21% (mainly due to falling oil revenue), expenditure 8.1 trillion roubles – up 34% (mainly due to increased military costs), creating a deficit 2.4 trillion roubles – ($29.4 billion)[171]

Following Central Bank of Russia interventions, the exchange rate of the rouble against the dollar remained relatively stable in 2022, although in 2023 it started to decrease significantly, reaching RUB 97 per USD 1 on 15 August 2023. Both the interventions and the exchange rate decrease resulted in significant criticism of the Central Bank by Russian state propaganda.[172] Quarter 2 of 2023 saw a 13% fall in the value of the rouble against the dollar and a current account surplus estimated in to be falling by 80% from the annual 2022 surplus of $233 billion.[173]

After 11 years of negotiations, on 8 June 2023, in Sochi, Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan signed the Commonwealth of Independent States Agreement on Free Trade in Services, Establishment, Operations and Investment to partly integrate Uzbekistan and Tajikistan on the common standards of the WTO (General Agreement on Trade in Services) and the EAEU (some provisions were borrowed from EAEU law) even without their membership in the WTO (Uzbekistan) or the EAEU (Uzbekistan and Tajikistan).[174] The Treaty on the Eurasian Economic Union has preserved international agreements on trade in services in the sphere of national competence of the member states therefore, the EAEU is not a party to the agreement.

In August and September 2023, the Central Bank of Russia started raising the key lending rate, ending up at 13% in September, while USD to RUB exchange rate remained at RUB 95.[175] As of June 2023 share of Russia's exports to EU dropped to 1.7% while Russia's imports from EU dropped to 1.5%.[176] In October 2023 the "psychological barrier" of RUB 100 per USD 1 was crossed.[177] In July 2024 the Russian Central Bank raised the key interest rate to 18%.[178]

The 2024 budget expects revenues of 35 trillion rubles ($349 billion) with expenditure of 36.6 trillion, based on a Urals oil forecast of $71.30 per barrel, a 90.1 rubles to USD 1 exchange rate and inflation of 4.5%. Defence spending will double to 10.78 trillion, 29.4% of expenditure. Russia currently has a record low unemployment rate of just 3 percent,[179] due to a demographic decline, demands of the war for industrial and military manpower, and large scale emigration.

In January 2025, it was reported that Russia had used a two-prong strategy to finance the large costs of the Russo-Ukrainian war since early 2022. In addition to the official Russian government defense budget —direct financial expenditure for waging the war was estimated at US$250 billion through June 2024 [180], rising to over 20% of annual GDP—an off-budget financing mechanism was employed to fund the war with over US$200 billion from preferential bank loans made to defence contractors and war-related businesses, loans compelled by the Russian government.[181][182]

-

Gross domestic product (PPP) per capita in April 2022

-

Unemployment rate of Russia since the fall of the Soviet Union

-

Russian inflation rate 2012–2022

Data

The following table shows the main economic indicators in 1980–2023.[183]

| Year | GDP (in billion. US$PPP) |

GDP per capita (in US$ PPP) |

GDP (in billion US$ nominal) |

GDP per capita (in US$ nominal) |

GDP growth (real) |

Inflation rate (in Percent) |

Unemployment (in Percent) |

Government debt (in % of GDP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | 1,602.6 | 10,805.2 | 71.6 | 482.8 | n/a | n/a | 5.2% | n/a |

| 1993 | n/a | |||||||

| 1994 | n/a | |||||||

| 1995 | n/a | |||||||

| 1996 | n/a | |||||||

| 1997 | 51.5% | |||||||

| 1998 | ||||||||

| 1999 | ||||||||

| 2000 | ||||||||

| 2001 | ||||||||

| 2002 | ||||||||

| 2003 | ||||||||

| 2004 | ||||||||

| 2005 | ||||||||

| 2006 | ||||||||

| 2007 | ||||||||

| 2008 | ||||||||

| 2009 | ||||||||

| 2010 | ||||||||

| 2011 | ||||||||

| 2012 | ||||||||

| 2013 | ||||||||

| 2014 | ||||||||

| 2015 | ||||||||

| 2016 | ||||||||

| 2017 | ||||||||

| 2018 | ||||||||

| 2019 | ||||||||

| 2020 | ||||||||

| 2021 | ||||||||

| 2022 | ||||||||

| 2023 |

Income inequality

In Russia, areas where income is higher have increased air pollution. However while income may have been higher in these regions a greater disparity in income inequality was found. It was discovered that "greater income inequality within a region is associated with more pollution, implying that it is not only the level of income that matters but also its distribution".[184] In Russia areas lacking in hospital beds suffer from greater air pollution than areas with higher numbers of beds per capita which implies that the poor or inadequate distribution of public services also may add to the environmental inequality of that region.[184]

Currency and monetary policy

On 25 December 1993, the Constitution of the Russian Federation came into force, where the main provisions were prescribed in the Article 75. The currency in the Russian Federation is the ruble. Monetary emission is carried out exclusively by the Central Bank of the Russian Federation (the Bank of Russia). The introduction and emission of other money in the Russian Federation is not allowed. The protection and ensuring the stability of the ruble is the main function of the Central Bank of the Russian Federation, which it carries out independently of other government bodies.[185] On 1 September 2013, the Bank of Russia also became a regulator of financial markets, applying the integrated model of financial sector supervision. [186]

The Central Bank of the Russian Federation follows inflation targeting policy. Higher inflation than in developed countries has remained throughout the last 25–30 post-Soviet years and the devaluation of the currency (in relation to foreign currencies and in relation to domestic goods) is significantly compensated by higher interest rates and an increase in nominal incomes and assets. This situation is typical for developing markets. Typically devaluations of the ruble relative to foreign currency strongly stimulate the export-oriented economy of Russia.

Exchange rate

The currency exchange rate of the Russian ruble is floating.

In 2011, the Bank of Russia, which was then headed by Sergei Ignatiev, took a course towards abolishing the currency corridor and designated a transition to a floating exchange rate for the ruble. Already under the new head of the Central Bank of the Russian Federation, Elvira Nabiullina, it was planned to complete the transition to a floating exchange rate regime from 1 January 2015. The Bank of Russia dismantled the currency corridor two months earlier - on 10 November 2014, so as not to waste gold and foreign exchange reserves.[187]

Ruble's Real Effective Exchange Rate remains in 2022–24 higher and stronger than in 1994 and 1998[188] when the sharp devaluations happened relative to the foreign currency.

Public policy

Federal, regional and municipal budgets

Fiscal policy

Russia was expected to have a Government Budget deficit of $21 billion in 2016.[189] The budget deficit narrowed to 0.6% of GDP in 2017 from 2.8% in 2016.[190]

Debts

Russia is a creditor nation and has a positive net international investment position (NIMP). Russia has one of the lowest government debts (total external and domestic) and lowest external debts (total public and private) among major economies.[191][192][193][194]

In 2022, domestic government debt increased by 13.9 percent to 18.78 billion rubles.[195] Russia Domestic government Debt data was reported at RUB 19,801.921 billion in May 2023.[196]

In 2022, the share of external debt to GDP was 17%, decreasing from 26.3% in 2021.[193][197] Russia's external debt was estimated at 381.8 billion U.S. dollars as of 1 January 2023, down 20.8 percent from the previous year.[198] Russia External Debt reached USD 357.9 billion in March 2023, compared with USD 380.5 billion in the previous quarter.[199]

National wealth fund

On 1 January 2004, the Government of Russia established the Stabilization fund of the Russian Federation as part of the federal budget to balance it if price of oil falls. On 1 February 2008, the Stabilization fund was divided into two parts. The first is a reserve fund equal to 10% of GDP and was to be invested in a similar way as the Stabilization Fund. The second is the National Welfare Fund of the Russian Federation to be invested in more risky instruments, including some shares in domestic and foreign companies. The Reserve fund which started with $125 billion was exhausted by 2017 and discontinued. The National Wealth Fund had started with $32 billion in 2008 and by August 2022, peaked at $201 billion.[200] December 2023 saw it fall to $133 billion with liquid assets also down at $56 billion.[201]

Corruption

Russia was the lowest rated European country in Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index for 2020; ranking 129th out of 180 countries.[202] Corruption is perceived as a significant problem in Russia,[203] affecting various aspects of life, including the economy,[204] business,[205] public administration,[206][207] law enforcement,[208] healthcare,[209] and education.[210] The phenomenon of corruption is strongly established in the historical model of public governance in Russia and attributed to general weakness of rule of law in Russia.[211] As of 2020, the percentage of business owners who distrust law enforcement agencies rose to 70% (from 45% in 2017); 75% don't believe in impartiality of courts and 79% do not believe that legal institutions protect them from abuse of law such as racketeering or arrest on dubious grounds.[212]

Sectors

Primary

Energy

The mineral-packed Ural Mountains and the vast fossil fuel (oil, gas, coal), and timber reserves of Siberia and the Russian Far East make Russia rich in natural resources, which dominate Russian exports. Oil and gas exports, specifically, continue to be the main source of hard currency.

Russia has been widely described as an energy superpower;[33] as it has the world's largest natural gas reserves,[34] the second-largest coal reserves,[35] the eighth-largest oil reserves,[36] and the largest oil shale reserves in Europe.[37] It is the world's leading natural gas exporter,[38] the second-largest natural gas producer,[39] the second-largest oil exporter[40] and producer,[41] and the third largest coal exporter.[42] Fossil fuels cause most of the greenhouse gas emissions by Russia.[213] The country is the world's fourth-largest electricity producer,[214] and the ninth-largest renewable energy producer in 2019.[215] Russia was also the world's first country to develop civilian nuclear power, and built the world's first nuclear power plant.[216] In 2019, It was the world's fourth-largest nuclear energy producer.[217] After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Russian state nuclear conglomerate Rosatom became the dominant actor in international nuclear power markets, training experts, constructing nuclear power plants, supplying fuel and taking care of spent fuel in around the world.[218] Whereas oil and gas were subject to international sanctions after Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2023, its nuclear industry was not targeted by sanctions.[218]

In the mid-2000s, the share of the oil and gas sector in GDP was around 20%, and in 2013 it was 20–21% of GDP.[219] The share of oil and gas in Russia's exports (about 50%) and federal budget revenues (about 50%) is large, and the dynamics of Russia's GDP are highly dependent on oil and gas prices,[220] but the share in GDP is much less than 50%. According to the first such comprehensive assessment published by the Russian statistics agency Rosstat in 2021, the maximum total share of the oil and gas sector in Russia's GDP, including extraction, refining, transport, sale of oil and gas, all goods and services used, and all supporting activities, amounts to 16.9% in 2017, 21.1% in 2018, 19.2% in 2019 and 15.2% in 2020. To compare the data obtained using the same methodology, the source provides data for other countries. This is more than the share of GDP in the United States (8%) and Canada (less 10%). This is comparable to the share of GDP in Norway (14%) and Kazakhstan (13.3%). It is much lower than the share of GDP in the United Arab Emirates (30%) and Saudi Arabia (50%). This assessment did not include, for example, the production of used pumps or specialized education, which should have been included, according to experts.[221][222][223][224][225] Russia consumes domestically two-thirds of its gas production and a quarter of its oil production while it sells three-quarters of its oil on the world market and Russia's share of the traded world oil market is 17.5% - more than Saudi Arabia's.[226][227] At the same time, experts note that there are formal and informal part of the rent and the total oil and gas rent in 2023 can be estimated at 24% of Russia's GDP. Michael Alexeyev (son of Lyudmila Alexeyeva), a professor of economics at Indiana University, notes that the oil and gas taxes reported by the government do not include corporate dividends and the so-called indirect or additional revenues derived from the expenditure of oil and gas rents in the economy.[228] There is also such an indicator as the oil rent (% of GDP), which is published by the World Bank. It is 9.7% for Russia, 14.8% for Kazakhstan, 6.1% for Norway, 23.7% for Saudi Arabia, 15.7% for the United Arab Emirates, 2.8% for Canada and 0.6% for the United States.[229]

2023 saw a fall in Russia's oil and gas tax revenues of 24% to 8.8 trillion roubles ($99.4 billion) compared to 2022.[230]

Mining

Russia is also a leading producer and exporter of minerals and gold. Russia is the largest diamond-producing nation in the world, estimated to produce over 33 million carats in 2013, or 25% of global output valued at over $3.4 billion, with state-owned ALROSA accounting for approximately 95% of all Russian production.[231]

In 2019, the country was the 3rd world producer of gold;[232] 2nd worldwide producer of platinum;[233] 4th worldwide producer of silver;[234] 9th largest world producer of copper;[235] 3rd largest world producer of nickel;[236] 6th largest world producer of lead;[237] 9th largest world producer of bauxite;[238] 10th largest world producer of zinc;[239] 2nd worldwide producer of vanadium;[240] 2nd largest world producer of cobalt;[241] 5th largest world producer of iron ore;[242] 7th largest world producer of boron;[243] 9th largest world producer of molybdenum;[244] 13th largest world producer of tin;[245] 3rd largest world producer of sulfur;[246] 4th largest world producer of phosphate;[247] 8th largest world producer of gypsum;[248] in addition to being the world's 10th largest producer of salt.[249] It was the world's 6th largest producer of uranium in 2018.[250]

Agriculture

Russia's agriculture sector contributes about 5% of the country's total GDP, although the sector employs about one-eighth of the total labour force.[251] It has the world's third-largest cultivated area, at 1,265,267 square kilometres (488,522 sq mi). However, due to the harshness of its environment, about 13.1% of its land is agricultural,[1] and only 7.4% of its land is arable.[252] The main product of Russian farming has always been grain, which occupies considerably more than half of the cropland.[251] Russia is the world's largest exporter of wheat,[253] and is the largest producer of barley,[254] buckwheat, oats,[255] and rye,[256] and the second-largest producer of sunflower seed.[257] Various analysts of climate change adaptation foresee large opportunities for Russian agriculture during the rest of the 21st century as arability increases in Siberia, which would lead to both internal and external migration to the region.[258]

More than one-third of the sown area is devoted to fodder crops, and the remaining farmland is devoted to industrial crops, vegetables, and fruits.[251] Owing to its large coastline along three oceans, Russia maintains one of the world's largest fishing fleets, ranking sixth in the world in tonnage of fish caught; capturing 4.77 million tonnes (4.69 million long tons; 5.26 million short tons) of fish in 2018.[259] It is also home to the world's finest caviar (the beluga), and produces about one-third of all canned fish, and some one-fourth of the world's total fresh and frozen fish.[251]

Industry

Defence industry

The defence industry of Russia is a strategically important sector and a large employer in the country. Russia has a large and sophisticated arms industry, capable of designing and manufacturing high-tech military equipment, including a fifth-generation fighter jet, nuclear powered submarines, firearms, and short range/long range ballistic missiles. It is the world's second-largest exporter of arms, behind only the United States.[1]

Aerospace

Aircraft manufacturing is an important industry sector in Russia, employing around 355,300 people. The Russian aircraft industry offers a portfolio of internationally competitive military aircraft such as MiG-29 and Su-30, while new projects such as the Sukhoi Superjet 100 are hoped to revive the fortunes of the civilian aircraft segment. In 2009, companies belonging to the United Aircraft Corporation delivered 95 new fixed-wing aircraft to its customers, including 15 civilian models. In addition, the industry produced over 141 helicopters. It is one of the most science-intensive hi-tech sectors and employs the largest number of skilled personnel. The production and value of the military aircraft branch far outstrips other defence industry sectors, and aircraft products make up more than half of the country's arms exports.[260]

The Space industry of Russia consists of over 100 companies and employs 250,000 people.[261]

Automotive industry

Automotive production is a significant industry in Russia, directly employing around 600,000 people or 1% of the country's total workforce. Russia produced 1,767,674 vehicles in 2018, ranking 13th among car-producing nations in 2018, and accounting for 1.8% of the worldwide production.[262] Following the 2022 sanctions and the withdrawal of Western manufacturers the production dropped to 450,000 passenger cars in 2022, the lowest level since the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.[263] The main local brands are light vehicle producers AvtoVAZ and GAZ, while KamAZ is the leading heavy vehicle producer. In December 2022 the only foreign car manufacturers are eleven Chinese carmakers that have production operations or are constructing their plants in Russia.[264]

Electronics

Russia was experiencing a regrowth of microelectronics, with the revival of JCS Mikron until sanctions took effect in 2022.[265][266][267]

Services

Retail

As of 2013, Russians spent 60% of their pre-tax income on shopping, the highest percentage in Europe. This is possible because many Russians pay no rent or house payments, owning their own home after privatization of state-owned Soviet housing. Shopping malls were popular with international investors and shoppers from the emerging middle class. Russia had over 1,000 shopping malls in 2020, although in 2022, many international companies left Russia resulting in empty stores in malls.[268] A supermarket selling groceries is a typical anchor store in a Russian mall.[269]

Retail sales in Russia[270]

| Year | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total retail sales (RUB trillions) | 14.60 | 16.49 | 19.08 | 21.3 | 23.7 | 26.4 | 27.6 | 29.75 | 27.88 | 31.58 | 33.62 | 33.56 | 39.47 | 42.51 |

Telecommunications

Russia's telecommunications industry is growing in size and maturity. As of December 2007, there were an estimated 4,900,000 broadband lines in Russia.[271]

As of 2020[update], 122,488,468 Russians (85% of the country's total population) were Internet users.[272]

There are four national mobile phone networks, MegaFon, Tele2, Beeline and MTS with total subscriptions between 2011 and 2021 ranging between 200 and 240 million.[273]

Transportation

Railway transport in Russia is mostly under the control of the state-run Russian Railways.[274] The total length of common-used railway tracks is the world's third-longest, and exceeds 87,157 km (54,157 mi).[275] As of 2016[update], Russia has 1,452.2 thousand km of roads,[276] and its road density is among the world's lowest.[277] Russia's inland waterways are the world's second-longest, and total 102,000 km (63,380 mi).[278] Among Russia's 1,218 airports,[279] the busiest is Sheremetyevo International Airport in Moscow.[280]

Russia's largest port is the Port of Novorossiysk in Krasnodar Krai along the Black Sea.[281] Russia is the world's sole country to operate nuclear-powered icebreakers, which advance the economic exploitation of the Arctic continental shelf of Russia, and the development of sea trade through the Northern Sea Route.[282]

Construction

In 2022, construction was worth 13 trillion rubles, 5% more than in 2021. Residential construction in 2022 reached 126.7 million square metres (1,364 million square feet).[283]

The 2020–2030 target for construction is 1 billion square metres (1.1×1010 square feet) of housing, 20% of all housing stock to be renovated and to increase space from 27.8 square metres (299 sq ft) up to 33.3 square metres (358 sq ft) per person.[283]

Insurance

According to the Central Bank of Russia 422 insurance companies operate on the Russian insurance market by the end of 2013. The concentration of insurance business is significant across all major segments except compulsory motor third party liability market (CMTPL) [ru], as the top 10 companies in 2013 charged 58.1% premiums in total without compulsory health insurance (CHI).[284] Russian insurance market in 2013 demonstrated quite significant rate of growth in operations. Total amount of premiums charged (without CHI) in 2013 is RUB 904.9 bln (increase on 11.8% compared to 2012), total amount of claims paid is RUB 420.8 bln (increase on 13.9% compared to 2012). Premiums to GDP ratio (total without CHI) in 2013 increased to 1.36% compared to 1.31 a year before. The share of premiums in household spending increased to 1.39%. Level of claims paid on the market total without CHI is 46.5%, an insufficient increase compared to 2012. The number of policies in 2013 increased on 0.1% compared to 2012, to 139.6 mln policies.

Although relative indicators of the Russian insurance market returned to pre-crisis levels, the progress is achieved mainly by the increase of life insurance and accident insurance, the input of these two market segments in premium growth in 2013 largely exceeds their share on the market. As before, life insurance and accident insurance are often used by banks as an appendix to a credit contract protecting creditors from the risk of credit default in case of borrower's death or disability. The rise of these lines is connected, evidently, with the increase in consumer loans, as the total sum of credit obligations of population in 2013 increased by 28% to RUB 9.9 trillion. At the same time premium to GDP ratio net of life and accident insurance remained at the same level of 1.1% as in 2012. Thus, if "banking" lines of business are excluded, Russian insurance market is in stagnation stage for the last four years, as premiums to GDP ratio net of life and accident insurance remains at the same level of 1.1% since 2010.[285]

Information technology

The IT market is one of the most dynamic sectors of the Russian economy. Russian software exports have risen from just $120 million in 2000 to $3.3 billion in 2010.[287] Since the year 2000 the IT market has started growth rates of 30–40% a year, growing by 54% in 2006 alone. The biggest sector in terms of revenue is system and network integration, which accounts for 28.3% of the total market revenues.[288] Meanwhile, the fastest growing segment of the IT market is offshore programming.

The government has launched a program promoting construction of IT-oriented technology parks (Technoparks)—special zones that have an established infrastructure and enjoy a favorable tax and customs regime, in seven different locations: Moscow, Novosibirsk, Nizhny Novgorod, Kaluga, Tumen, Republic of Tatarstan and St. Peterburg Region.[287]

Under a government decree signed in June 2013, a special "roadmap" is expected to ease business suppliers' access to the procurement programs of state-owned infrastructure monopolies, including such large ones as Gazprom, Rosneft, Russian Railways, Rosatom, and Transneft. These companies will be expected to increase the proportion of domestic technology solutions they use in their operations. The decree puts special emphasis on purchases of innovation products and technologies. According to the new decree, by 2015, government-connected companies must double their purchases of Russian technology solutions compared to the 2013 level and their purchasing levels must quadruple by 2018.[289]

Russia is one of the few countries in the world with a homegrown internet search engine with a significant marketshare as the Russian-based search engine Yandex is used by 53.8% of internet users in the country.[290][291][292]

Known Russian IT companies are ABBYY (FineReader OCR system and Lingvo dictionaries), Kaspersky Lab (Kaspersky Anti-Virus, Kaspersky Internet Security), Mail.Ru (portal, search engine, mail service, Mail.ru Agent messenger, ICQ, Odnoklassniki social network, online media sources).

Tourism

According to a UNWTO report, Russia is the sixteenth-most visited country in the world, and the tenth-most visited country in Europe, as of 2018, with 24.6 million visits.[293] Russia is ranked 39th in the Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Report 2019.[294] According to Federal Agency for Tourism, the number of inbound trips of foreign citizens to Russia amounted to 24.4 million in 2019.[295] Russia's international tourism receipts in 2018 amounted to $11.6 billion.[293] In 2020, tourism accounted for about 4% of country's GDP.[296] Major tourist routes in Russia include a journey around the Golden Ring theme route of ancient cities, cruises on the big rivers like the Volga, and journeys on the famous Trans-Siberian Railway.[297] Russia's most visited and popular landmarks include Red Square, the Peterhof Palace, the Kazan Kremlin, the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius and Lake Baikal.[298]

Economic integration

|

| Top-4 largest economies (China, the US, India, Russia) in the world by PPP GDP in 2023 according to the World Bank, the members of the Eurasian Economic Union as well as Tajikistan and Uzbekistan that are forming a common market within the CIS (EAEU+2).[299] |

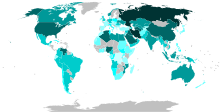

Russia joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) on 22 August 2012.[121] On 20 September 2012, the Free Trade Agreement of the Commonwealth of Independent States signed on 18 October 2011 came into force (CIS FTA) for Russia and superseded previous agreements.[124] Russia is a founding member of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) and is party to EAEU trade agreements with Vietnam, Iran, Singapore, and Serbia. In 2018, the EAEU signed a trade cooperation agreement with China, and it is in trade negotiations with India, Israel, and Egypt. Russia is also a party to several agreements that predate the EAEU.[300] The EAEU Treaty in 2015 superseded previous integration agreements and envisaged an economic union (the deepest stage of economic integration[125]). The EAEU provides for free movement of goods, services, capital and labour without a work permit ("four economic freedoms" as in the European Union), pursues coordinated, harmonized and single policy in the sectors determined by the Treaty and international agreements within the Union. The EAEU has a Eurasian Customs Union and an integrated single market of 183 million people.[126]

External trade and investment

Trade

Russia recorded a trade surplus of US$15.8 billion in 2013.[302] Balance of trade in Russia is reported by the Central Bank of Russia. Historically, from 1997 until 2013, Russia balance of trade averaged US$8.338billion reaching an all-time high of US$20.647 billion in December 2011 and a record low of −185 US$ million in February 1998. Russia runs regular trade surpluses primarily due to exports of commodities.

In 2015, Russia main exports are oil and natural gas (62.8% of total exports), ores and metals (5.9%), chemical products (5.8%), machinery and transport equipment (5.4%) and food (4.7%). Others include: agricultural raw materials (2.2%) and textiles (0.2%).[303]

Russia top exports in 2021 were: Crude oil $110.9b, Processed oil $69.9b, gold $17.3b, coal $15.4b and natural gas $7.3b.[304]

Russia top imports in 2021 were: Transmission equipment $10.7b, medication $7.3b, tankers $3.7b, parts and accessories for data processing 3.7b and storage units $3.3b.[304]

Foreign trade of Russia – Russian export and import[304]

| Year | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Export (US$ Billions) | 241 | 302 | 352 | 468 | 302 | 397 | 517 | 525 | 527 | 498 | 344 | 302 | 379 | 451 | 427 | 337 | 492 |

| Import (US$ Billions) | 99 | 138 | 200 | 267 | 171 | 229 | 306 | 316 | 315 | 287 | 183 | 207 | 260 | 240 | 247 | 231 | 293 |

| Top Trading Partners for Russia for 2021[304] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

2013–

In 2017, Russian Federation's commercial services' shares of total exports and imports were 13.9% and 26.8%, respectively. Russian Federation had a trade-to-GDP ratio of 46.6% in 2017.[305] In 2013–2017, Russia had a trade surplus for goods, and a trade deficit for services. Since trade in goods is larger than trade in services, Russia had a significant trade surplus.[306] Trade is relatively important to the Russian economy: the ratio of Russia's goods trade (exports plus imports) to GDP has averaged about 40% in recent years, compared to 20% for the United States. In 2021, Russia ranked 13th among world goods exporters and 22nd among importers. According to Russian official sources, its goods exports totaled $492 billion in 2021, up 46% from 2020 (not adjusting for inflation). Minerals, including oil and gas, made up nearly 45% of these exports. Goods imports rose by 27%, reaching $294 billion in 2021. Machinery and mechanical appliances topped the list of imports, accounting for almost a third of Russia's goods imports. In services trade, Russia ranked 26th among world exporters and 19th among importers in 2020, the most recent year for which data is available. The country was a net importer of services, exporting $49 billion worth of services and importing $76 billion.[300]

According to the World Bank, imports of goods and services accounted for 21.3% of Russia's gross domestic product (GDP) in 2021,[307] while exports made up 30.9%.[308] Russia has trade-to-GDP ratio (trade openness) 49.26% [309] which is below the global average. In a December 2022 study, an economist from the Bank of Russia's Research and Forecasting Department found that Russia's import dependence is relatively low, does not exceed the median for other countries and the share of imports in most industries is lower than in other countries. The key explanation for this could be the low involvement of the Russian economy in global value supply chains and its focus on production of raw materials. However, 60% of Russia's imports come from the countries that have imposed sanctions against it.[170]

Mergers and acquisitions

Between 1985 and 2018, almost 28,500 mergers or acquisitions have been announced in Russia. This cumulates to an overall value of around USD 984 billion which translates to RUB 5.456 billion. In terms of value, 2007 has been the most active year with USD 158 billion, whereas the number of deals peaked in 2010 with 3,684 (964 compared to the value record year 2007). Since 2010 value and numbers have decreased constantly and another wave of M&A is expected.[310]

The majority of deals in, into or out of Russia have taken place in the financial sector (29%), followed by banks (8.6%), oil and gas (7.8%), and Metals and Mining (7.2%).

Here is a list of the top deals with Russian companies participating ranked by deal value in million USD:

| Date Announced | Acquiror Name | Acquiror Mid Industry | Acquiror Nation | Target Name | Target Mid Industry | Target Nation | Value of Transaction ($mil) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 October 2012 | Rosneft Oil Co | Oil & gas | Russian Fed | TNK-BP Ltd | Oil & gas | Russian Fed | 27854.12 |

| 24 July 2012 | Rosneft Oil Co | Oil & gas | Russian Fed | TNK-BP Ltd | Oil & gas | Russian Fed | 26061.15 |

| 22 April 2003 | Yukosneftegaz | Oil & gas | Russian Fed | Sibirskaia Neftianaia Co | Oil & gas | Russian Fed | 13615.23 |

| 28 September 2005 | Gazprom | Oil & gas | Russian Fed | Sibneft | Oil & gas | Russian Fed | 13101.08 |

| 13 April 2005 | Shareholders | Other financials | Russian Fed | Polyus | Metals & mining | Russian Fed | 12867.39 |

| 16 December 2010 | MMC Norilsk Nickel PJSC | Metals & mining | Russian Fed | MMC Norilsk Nickel PJSC | Metals & mining | Russian Fed | 12800 |

| 27 July 2007 | Shareholders | Other financials | Russian Fed | HydroOGK | Power | Russian Fed | 12381.83 |

| 10 December 2016 | QHG Shares Pte Ltd | Other financials | Singapore | Rosneft Oil Co | Oil & gas | Russian Fed | |

| 30 June 2010 | KazakhGold Group Ltd | Metals & mining | Kazakhstan | Polyus Zoloto | Metals & mining | Russian Fed | 10261.33 |

| 5 August 2008 | Vladimir Potanin | Other financials | Russian Fed | MMC Norilsk Nickel PJSC | Metals & mining | Russian Fed | 10021.11 |

The majority of the top 10 deals are within the Russian oil and gas sector, followed by metals and mining.

See also

- History of Russia (1991–present)

- Federal government of Russia

- List of companies of Russia

- List of Russian federal districts by GDP

- Monotown, a town whose economy is dominated by a single industry or company. The term is sometimes used regarding some towns in Russia

- Politics of Russia

- Taxation in Russia

- Types of legal entities in Russia

- Unitary enterprise, a government-owned corporation in Russia and some other post-Soviet states

- List of federal subjects of Russia by GDP per capita

Notes

References

- ^ a b c d "Russia". CIA.gov. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

- ^ a b "World Economic Outlook Database - Groups and Aggregates Information". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 5 August 2024.

- ^ "World Bank Country and Lending Groups". datahelpdesk.worldbank.org. World Bank. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ Not including 2,482,450 people living in annexed Crimea Том 1. Численность и размещение населения. Russian Federal State Statistics Service (in Russian). Archived from the original on 24 January 2020. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g "World Economic Outlook database: October 2024". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund.

- ^ a b "Central Intelligence Agency". Cia.gov. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^ "Poverty headcount ratio at national poverty lines (% of population) – Russian Federation". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ "Gini index (World Bank estimate) – Russian Federation". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Archived from the original on 13 May 2020. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ "Human Development Index (HDI)". hdr.undp.org. HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. Archived from the original on 15 December 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ "Inequality-adjusted HDI (IHDI)". hdr.undp.org. UNDP. Archived from the original on 25 June 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ a b "Labor force, total – Russia". World Bank & ILO. Archived from the original on 28 March 2023. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ^ "Employment to population ratio, 15+, total (%) (national estimate) – Russia". World Bank. Archived from the original on 25 January 2023. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ a b Marrow, Alexander; Korsunskaya, Darya (5 June 2024). "Soaring wages, record-low unemployment underscore Russia's labour squeeze". Reuters. Retrieved 4 August 2024.

Russia's unemployment rate dropped to a record-low 2.6% in April and real wages soared in March, data published by the federal statistics service showed on Wednesday, highlighting the extent of Russia's tight labour market.

- ^ "Exports of goods and services (BoP, current US$) - Russian Federation". World Bank. World Bank Group. Retrieved 5 August 2024.

- ^ "Export Partners of Russia". The Observatory of Economic Complexity. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ "Imports of goods and services (BoP, current US$) - Russian Federation". World Bank. World Bank Group. Retrieved 5 August 2024.

- ^ "Import Partners of Russia". The Observatory of Economic Complexity. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ a b "UNCTAD 2022" (PDF). UNCTAD. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 December 2022. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects:April 2024". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 5 August 2024.

- ^ "External Debt | Economic Indicators | CEIC". www.ceicdata.com. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ Korsunskaya, Darya; Marrow, Alexander (17 February 2023). "Russia stands by 2% of GDP budget deficit plan after huge Jan shortfall". Reuters. Archived from the original on 27 February 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ "Sovereigns rating list". Standardandpoors.com. Standard & Poor's. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ "Russia on Cusp of Exiting Junk as S&P Outlook Goes Positive". Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg L.P. 17 March 2017. Archived from the original on 31 August 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^ "Moody's changes outlook on Russia's Ba1 government bond rating to stable from negative". Moody's. 17 February 2017. Archived from the original on 18 February 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^ "Russia's Outlook Raised to Stable by Fitch on Policy Action". Bloomberg. 14 October 2016. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^ "International Reserves of the Russian Federation (End of period)". Central Bank of Russia. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 13 January 2023.

- ^ "World Bank Country and Lending Groups – World Bank Data Help Desk". datahelpdesk.worldbank.org. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ "Industrial countries". Oxford Reference. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 3 August 2024.

...and the countries of the former Soviet Union and Central and Eastern Europe, of which several, including Russia and the Czech Republic, are heavily industrialized.

- ^

—Rosefielde, Steven, and Natalia Vennikova. "Fiscal Federalism in Russia: A Critique of the OECD Proposals". Cambridge Journal of Economics, vol. 28, no. 2, Oxford University Press, 2004, pp. 307–18, JSTOR 23602130.

—Robinson, Neil. "August 1998 and the Development of Russia's Post-Communist Political Economy". Review of International Political Economy, vol. 16, no. 3, Taylor & Francis, Ltd., 2009, pp. 433–55, JSTOR 27756169.

—Charap, Samuel. “No Obituaries Yet for Capitalism in Russia". Current History, vol. 108, no. 720, University of California Press, 2009, pp. 333–38, JSTOR 45319724.

—Rutland, Peter. "Neoliberalism and the Russian Transition". Review of International Political Economy, vol. 20, no. 2, Taylor & Francis, Ltd., 2013, pp. 332–62, JSTOR 42003296.

—Kovalev, Alexandre, and Alexandre Sokalev. "Russia: Towards a Market Economy". New Zealand International Review, vol. 18, no. 1, New Zealand Institute of International Affairs, 1993, pp. 18–21, JSTOR 45234200.

—Czinkota, Michael R. "Russia's Transition to a Market Economy: Learning about Business". Journal of International Marketing, vol. 5, no. 4, American Marketing Association, 1997, pp. 73–93, JSTOR 25048706. - ^ Turak, Natasha (23 June 2022). "Russia's ruble hit its strongest level in 7 years despite massive sanctions. Here's why". CNBC. Archived from the original on 14 February 2023. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- ^ "Russia becomes WTO member after 18 years of talks". BBC News. 16 December 2011. Archived from the original on 1 December 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- ^ Excerpted from Curtis, Glenn E., ed. (1998). "Russia – Natural Resources". Country Studies US. Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 13 March 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

Russia is one of the world's richest countries in raw materials, many of which are significant inputs for an industrial economy. Russia accounts for around 20 per cent of the world's production of oil and natural gas and possesses large reserves of both fuels. This abundance has made Russia virtually self-sufficient in energy and a large-scale exporter of fuels.

- ^ a b "The Future of Russia as an Energy Superpower". Harvard University Press. 20 November 2017. Archived from the original on 2 December 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ^ a b "Russia". International Energy Agency (IEA). 8 August 2024.

Russia is the world's second-largest producer of natural gas, behind the United States, and has the world's largest gas reserves.

- ^ a b "Statistical Review of World Energy 69th edition" (PDF). bp.com. BP. 2020. p. 45. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 September 2020. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Crude oil – proved reserves". CIA World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ a b 2010 Survey of Energy Resources (PDF). World Energy Council. 2010. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-946121-021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Natural gas – exports". CIA World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 5 April 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ a b "Natural gas – production". CIA World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ a b "Crude oil – exports". CIA World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ a b "Crude oil – production". CIA World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ a b Overland, Indra; Loginova, Julia (1 August 2023). "The Russian coal industry in an uncertain world: Finally pivoting to Asia?". Energy Research & Social Science. 102: 103150. Bibcode:2023ERSS..10203150O. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2023.103150. ISSN 2214-6296.

- ^ "International Reserves of the Russian Federation (End of period)". Central Bank of Russia. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ Wezeman, Pieter D.; Djokic, Katarina; George, Mathew; Hussain, Zain; Wezeman, Siemon T. (March 2024). "Trends in International Arms Transfers, 2023" (PDF). Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI).

The five largest exporters were the United States, France, Russia, China and Germany.

- ^ "Russian oil and gas revenue soars 41% in first half, data shows". Reuters. 3 July 2024. Retrieved 8 August 2024.

Proceeds from oil and gas sales for Russia's federal budget rose by around 41% year on year in the first half of the year 5.698 trillion roubles ($65.12 billion), finance ministry data showed on Wednesday...

- ^ "Fuel exports (% of merchandise exports) - Russian Federation". World Bank. Retrieved 8 August 2024.

- ^ "Russian Federation". United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Retrieved 5 August 2024.

Russian Federation's HDI value for 2022 is 0.821— which put the country in the Very High human development category—positioning it at 56 out of 193 countries and territories.

- ^ "Final consumption expenditure (% of GDP) – Russia". World Bank. Retrieved 5 August 2024.

- ^ "Household final consumption expenditure (current US$) | Data". World Bank. Retrieved 5 August 2024.

- ^ "Public social protection expenditure (%of GDP)". World Bank. World Bank Group. Retrieved 9 August 2024.

- ^ "Forbes Billionaires 2021". Forbes. Archived from the original on 4 January 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ Russell, Martin (April 2018). "Socioeconomic inequality in Russia" (PDF). European Parliamentary Research Service. European Parliament. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 February 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ Remington, Thomas F. (March 2015). "Why is interregional inequality in Russia and China not falling?". Communist and Post-Communist Studies. 48 (1). University of California Press: 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.postcomstud.2015.01.005. JSTOR 48610321.

- ^ Kholodilin, Konstantin A.; Oshchepkov, Aleksey; Siliverstovs, Boriss (2012). "The Russian Regional Convergence Process: Where Is It Leading?". Eastern European Economies. 50 (3). Taylor & Francis: 5–26. doi:10.2753/EEE0012-8775500301. JSTOR 41719700. S2CID 153168354.

- ^ Schulze, Günther G.; Sjahrir, Bambang Suharnoko; Zakharov, Nikita (February 2016). "Corruption in Russia". The Journal of Law and Economics. 59 (1). The University of Chicago Press: 135–171. doi:10.1086/684844. JSTOR 26456942.

- ^ Kapeliushnikov, Rostislav I. (3 October 2023). "The Russian labor market: Long-term trends and short-term fluctuations". Russian Journal of Economics. 9 (3). Voprosy Ekonomiki: 245–270. doi:10.32609/j.ruje.9.113503.

- ^ Mikhailova, Olga; Safarova, Gaiane; Safarova, Anna (2018). "Population ageing and policy responses in the Russian Federation" (PDF). International Journal on Ageing in Developing Countries. 3 (1). International Institute on Aging: 6–26.

- ^ "A Russia without Russians? Putin's disastrous demographics". Washington, D.C.: Atlantic Council. 7 August 2024. Retrieved 9 August 2024.

- ^ Walsh, Ben (9 March 2022). "The unprecedented American sanctions on Russia, explained". Vox. Archived from the original on 11 April 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ Luzin, Pavel; Prokopenko, Alexandra (11 October 2023). "Russia's 2024 Budget Shows It's Planning for a Long War in Ukraine". Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved 3 August 2024.

The war against Ukraine and the West is not only the Kremlin's biggest priority; it is now also the main driver of Russia's economic growth.

- ^ Kurbangaleeva, Ekaterina (28 May 2024). "Russia's Soaring Wartime Salaries Are Bolstering Working-Class Support for Putin". Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved 4 August 2024.

- ^ Rosenberg, Steve (6 June 2024). "Russia's economy is growing, but can it last?". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 3 August 2024.

- ^ Gorodnichenko, Yuriy; Korhonen, Likka; Ribakova, Elina (24 May 2024). "The Russian economy on a war footing: A new reality financed by commodity exports". London, United Kingdom: Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR). Retrieved 3 August 2024.

- ^ Richard Connolly, The Russian economy: a very short introduction (2020) pp 2–11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Zhuravskaya, Ekaterina; Guriev, Sergei; Markevich, Andrei (2024). "New Russian Economic History". Journal of Economic Literature. 62 (1): 47–114. doi:10.1257/jel.20221564. ISSN 0022-0515.

- ^ a b c d Broadberry, Stephen; Korchmina, Elena (2024). "Catching-Up and Falling Behind: Russian Economic Growth, 1690s–1880s". The Journal of Economic History. doi:10.1017/S0022050724000287. ISSN 0022-0507.

- ^ Goldsmith, Raymond W. (1961). "The Economic Growth of Tsarist Russia 1860-1913". Economic Development and Cultural Change. 9 (3): 441–475. ISSN 0013-0079.

- ^ "Economic Thought in Russia". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2 (2): 233–243. 1888. doi:10.2307/1879493. ISSN 0033-5533.

- ^ Davies 1998, p. 1, 3.

- ^ Appel, Hilary; Orenstein, Mitchell A. (2018). From Triumph to Crisis: Neoliberal Economic Reform in Postcommunist Countries. Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-1108435055. Archived from the original on 5 March 2024. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ a b "Nuffield Poultry Study Group — Visit to Russia 6th–14th October 2006" (PDF). The BEMB Research and Education Trust. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 August 2007. Retrieved 27 December 2007.

- ^ "How Harvard lost Russia". Institutional Investor. 27 February 2006. Archived from the original on 17 July 2014. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- ^ Mattei, Clara E. (2022). The Capital Order: How Economists Invented Austerity and Paved the Way to Fascism. University of Chicago Press. p. 302. ISBN 978-0226818399. Archived from the original on 4 January 2023. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d "GDP growth (annual %)". World Bank. Archived from the original on 28 June 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- ^ "Members". APEC Study Center; City University of Hong Kong. Archived from the original on 10 August 2007. Retrieved 27 December 2007.

- ^ Weber, Isabella (2021). How China escaped shock therapy : the market reform debate. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-429-49012-5. OCLC 1228187814.

- ^ Scheidel, Walter (2017). The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century. Princeton University Press. p. 222. ISBN 978-0691165028.

- ^ Privatisation 'raised death rate' Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. BBC, 15 January 2009. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- ^ Rosefielde, Steven (2001). "Premature Deaths: Russia's Radical Economic Transition in Soviet Perspective". Europe-Asia Studies. 53 (8): 1159–1176. doi:10.1080/09668130120093174. S2CID 145733112.

- ^ Ghodsee, Kristen; Orenstein, Mitchell A. (2021). Taking Stock of Shock: Social Consequences of the 1989 Revolutions. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 195–196. doi:10.1093/oso/9780197549230.001.0001. ISBN 978-0197549247.

In the mortality belt of the European former Soviet Union, an aggressive health policy intervention might have prevented tens of thousands of excess deaths, or at least generated a different perception of Western intentions. Instead, Western self-congratulatory triumphalism, the political priority to irreversibly destroy the communist system, and the desire to integrate East European economies into the capitalist world at any cost took precedence.

- ^ Ghodsee, Kristen (2017). Red Hangover: Legacies of Twentieth-Century Communism. Duke University Press. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-0822369493. Archived from the original on 4 August 2018. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- ^ a b Weber, Isabella (2021). How China escaped shock therapy : the market reform debate. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-429-49012-5. OCLC 1228187814.